From Orient to Occident: Countess Setsuko Klossowska de Rola

13.08.2023 Profile, Traditions, Gstaad Living, Profile, Arts & CultureWhat the artist is always looking for is the mode of existence in which soul and body are one and indivisible: in which the outward is expressive of the inward: in which form reveals.

proclaimed Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) in De ...

What the artist is always looking for is the mode of existence in which soul and body are one and indivisible: in which the outward is expressive of the inward: in which form reveals.

proclaimed Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) in De Profundis (Latin: “Out of the Depths”). This is what I try to do when I paint or sculpt: I want my art to come the closest it can to the essence of things. The title of my exhibition this summer in Gstaad, Into Nature, refers not only to nature as the representation of the wild, but also nature as the intrinsic reality of beings. This philosophy of art is linked to the teachings that marked me indelibly in the postwar Japan of my youth. Even traditional martial arts or breathing techniques aim to unite the invisible spirit that inhabits us together with our bodies. Applied to our exterior reality, art serves the same purpose.

Working in both the fine and decorative arts allows me to better express myself. Take, for example, the bronze pomegranate chandeliers at Gagosian. The pomegranate is redolent of another time, most especially in the iconography of the Orient; be it in Persian manuscripts or jewels of the Mughal Empire. The decorative arts make everyday objects extraordinary: look no further than the magnificent collections both amassed and sadly dispersed by princes and potentates. The Al Thani Collection exhibited at the Hôtel de la Marine and his record-setting auction last year of French decorative arts from the Hôtel Lambert, both in Paris, are a case in point.

Living with these objects lends beauty to the quotidian, particularly when the styles of Orient and Occident coalesce. I see this coalescence in ancient Roman painting, in its conception of beauty, and in the stylised but simple rapport of light and shadow. This reinvented perspective of Orient and Occident is also evident in traditional Japanese painting. Particularly when I’m working on a still life, I consult ancient Roman scenes. Therein, I’m also attracted to plants with a sacred significance.

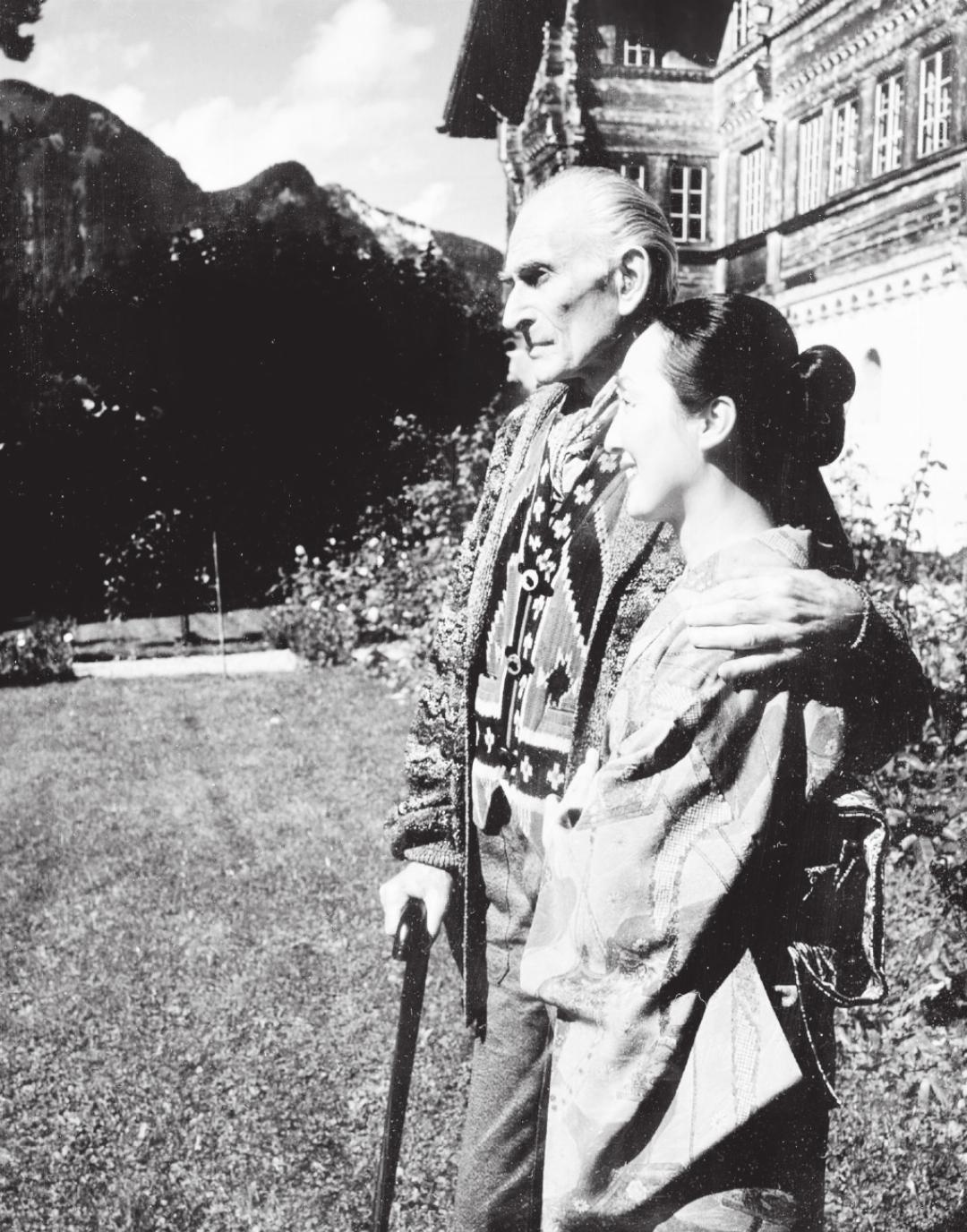

I echo your view, in these pages, of the Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977) exhibition this summer at The Jan Michalski Foundation. You describe it as an invitation to travel in time, across cultures as well as continents. Artistically, I see myself as having made a similar voyage. The new sculptures in my own summer exhibition here in Gstaad, themselves reminiscent of ancient Japanese ceramics, bear testament to this. I also mourn the disappearance of a former age: youth and the past. You see that here in my choice of photographs for this article. But I do celebrate the present in my work. For example, I first met Benoît Astier de Villatte as a baby in a pram at Rome’s Villa Medici. Now, my studio in Paris is at the ceramics firm that bears his name.

Passionate about my work which brings me unbridled joy and a real richness to my life, I’m indeed privileged which I never take for granted, but rather value.

Our post-modern existence – a kaleidoscope of colours, smells, and sounds – often overpowers the senses, evermore acutely. Technology is taking away our faculty for observation. I myself spend a great deal of time observing nature.

I take great comfort in the beauty that surrounds me in this region which has shaped me, very much as I shape terracotta: for example, in the sculptures opposite and overleaf.

Like my forebears, at times, I’m drawn to the monochrome silhouette, be it of a bare tree on the hill against the winter sky or in fashion – so forgiving of imperfections.

My own diffident manner is very much that of the Orient.

In a few years’ time, I will have lived here in this valley for fifty years. My husband’s gallerist in New York, Pierre Matisse (1900–1989), himself the son of the great French painter Henri Matisse (1869–1954), understood artists intimately. Just imagine a gentleman’s agreement in which he purchased our home here for us in exchange for my husband’s future output?

Born the same year as my husband, Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004) and his second wife, Martine Franck (1938–2012), were not only exceptional photographers but Gstaad habitués and close friends. Henri and Martine each honoured me with a portrait; his graces the front cover of this issue.

BY ALAN NAZAR IPEKIAN

Setsuko Klossowska de Rola

lives at the eighteenth century Le Grand Chalet de Rossinière since 1977. In 1979, she held her first solo exhibition at Galleria Il Gabbiano, Rome, later showing at Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York and the Lefevre Gallery in London. Her work is included in institutional collections such as that of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Since 2002, she has served as the honorary president of the Fondation Balthus, and in 2005 she was designated UNESCO’s Artist for Peace. Born in 1942, she attended the Jesuit-run Sophia University in Tokyo, learning about both Eastern and Western cultures, from Japanese calligraphy and Noh theatre to European literature and ballet. In 1962, having met her future husband who was visiting Japan for the first time, she relocated to Rome, where he was director of the French Academy at the Villa Medici, and began to paint.

Bibliography

Cf.: Diane Dorrans Saeks, Parisian by design, Rizzoli, New York, 2022, pgs. 204-9.

Next year, Gagosian will publish Setsuko Klossowska de Rola’s first monograph with the gallery, detailing her work from the 1960s through the present. The book will feature an essay by novelist Shan Sa. Aside from this, she authored nine books in Japan, including a children’s book that she both wrote and illustrated.

Exhibition in Gstaad until 10 September

Gagosian

Promenade 79

033 748 49 80

Gagosian.com

Open daily in August from 11am –1pm & 3– 6:30pm