MARIO TESTINO... up close

13.02.2026 Arts & Culture, Events, Profile, Lifestyle, Inspiration, Arts & CultureBEAUTY QUEENS, IN COWBELLS AND COLD LIGHT

Mario Testino speaks the way he photographs – calmly, with charm, and with an almost disarming generosity. Listening to him at the Patricia Low Contemporary vernissage, interviewed by Simon de Pury, who also curated the exhibition, you really felt what you often sense in his images: a mind that is visually intelligent without needing to announce itself.

His series “A Beautiful World” began, he told the room, as a desire for freedom. After decades in fashion, “45 years” in his words, he wanted a project that belonged to him. Not least because fashion, even at the highest level, always comes with someone else’s “yes” or “no”. He recalled being repeatedly told that his work was “too colourful” because editors wanted the images desaturated. The freedom to follow his own eye, he said, is “a treasure.”

That freedom is visible in the Swiss selection shown in Gstaad – and it starts, quite brilliantly, with cows.

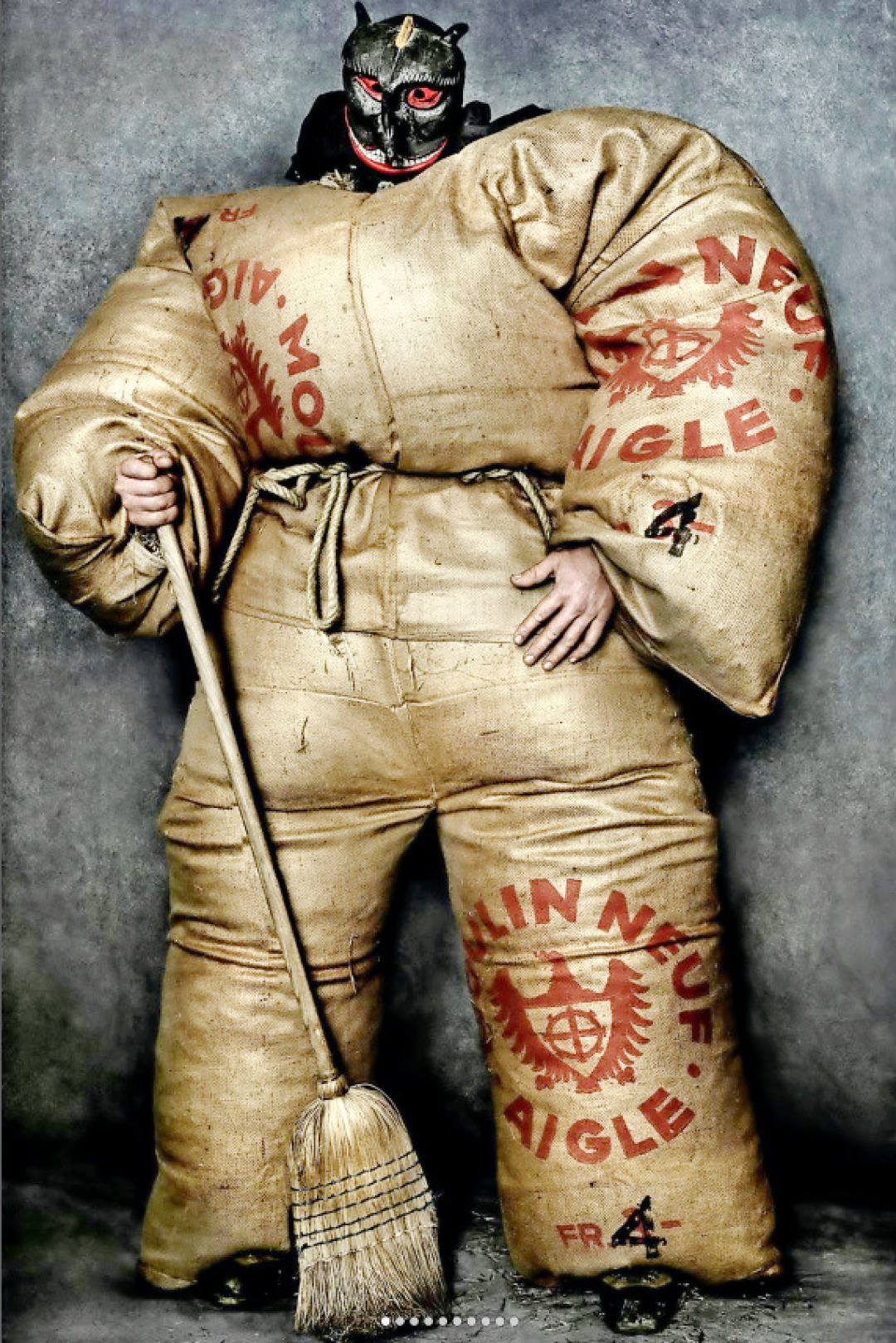

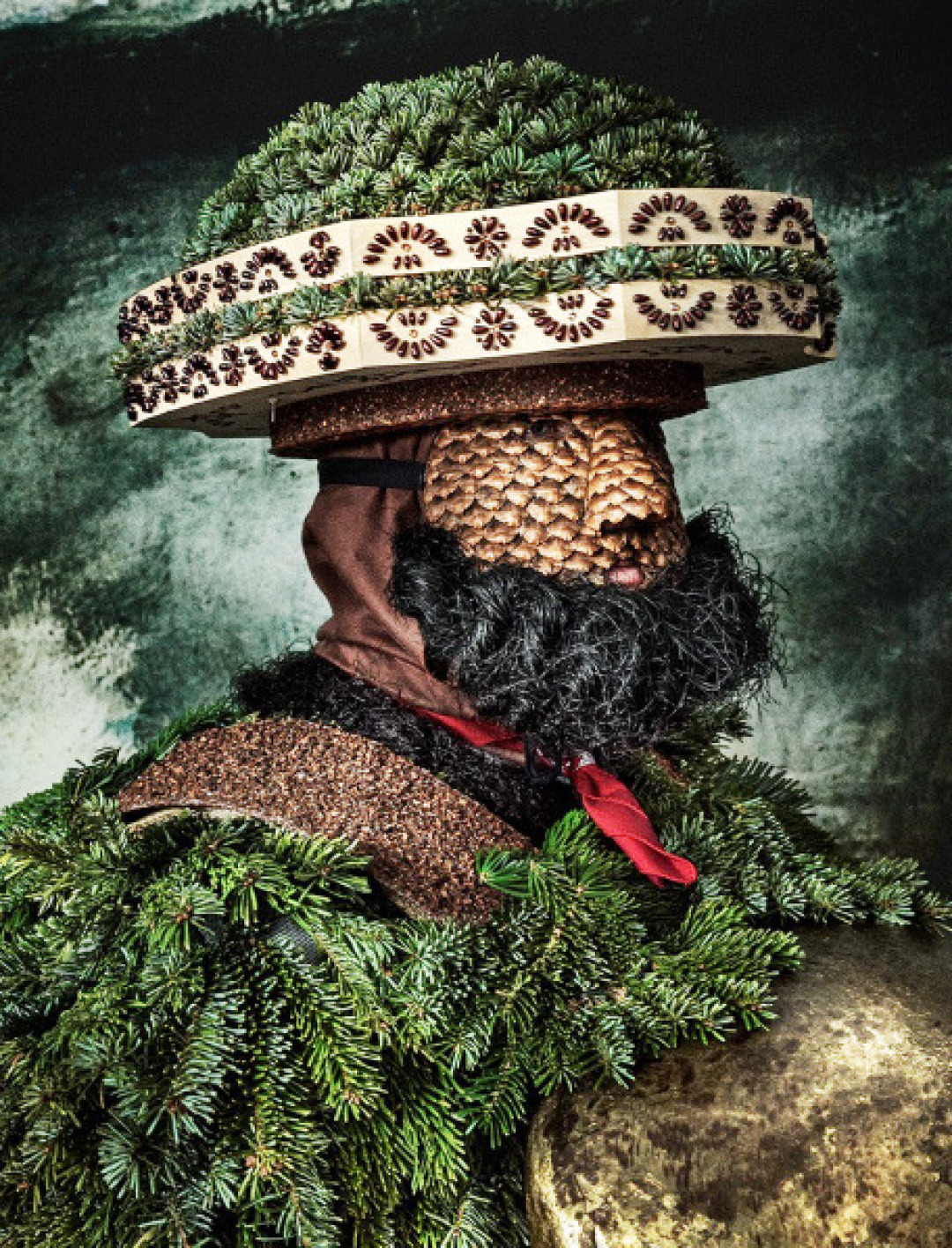

Testino described arriving in Switzerland almost with a cliché in mind – “Julie Andrews,” pretty dresses, an Alpine softness, until a friend sent him images of “odd-looking characters walking down the snow.” They looked, to him, almost aggressive. It didn’t fit his mental picture of the country, so he had to see for himself. He began on a farm, photographing cows – images that, he smiled, have become “very popular.”

The cows in this series are like portraits with ceremony. Their headpieces are flowers, structured, weighted, and read like formal dress. And Testino, who once spent mornings in fashion studios adjusting a lip line by millimetres, found himself noticing the equivalent details in an animal: he joked that his retouchers were alarmed when he began talking about the cows’ eyelashes.

It’s a funny moment, but it reveals something precise about this body of work: he is bringing the full seriousness of portraiture to subjects that are usually treated as “local colour.”

Beauty Queens

In fact, he went further. Watching Swiss cows being decorated, he began to wonder whether the animals register what is happening. Whether the ritual changes their posture the way a gown, jewellery, or black tie changes a person. He spoke about the strange communication we see online between animals and humans: whales, dolphins, foxes arriving for help and asked, quite sincerely, if these cows might feel that they are being paraded. He even considered naming the exhibition “Beauty Queens.” (He abandoned it, he laughed, after seeing the guild guards upstairs in the gallery.)

In Testino’s telling, tradition is not only a visual event but also a behavioural one. Dress codes alter the way we move and act; he believes the same may be true for animals at the centre of ritual. It’s a bold thought, delivered gently.

And he is methodical about how he makes these images.

For all the spontaneity of travel, Testino insisted that he researches each element deeply before arriving, ensuring he truly cares about what he’s going to photograph. Even the eagles displayed behind him, photographed in Mongolia, posed a practical conflict: handlers wanted him to use a long lens, but he prefers a standard lens – closer to how the human eye sees – which forced him to stand closer than they liked. His solution was characteristically direct: place the eagle, get close, and then use “noise” (raising his voice) to trigger attention – something he learned long ago, he said, because animals and children react to sound.

The series is not about chasing festival spectacle. Testino admitted he often works out of season: he seeks the exclusivity of attention and the space to direct. He told the room that in Brazil, when he wanted to photograph the carnival, a 300-person carnival was organised for him, not during the event but for his camera. He did something similar with the cows: it wasn’t spring, so there was concern the flowers wouldn’t be “right,” but they made it work. He is “less into the act of festivity,” he said, and more into the documentation of the outside of the festivity.

That line matters for the PLC edit. What you see upstairs in the gallery is far from reportage. It’s a controlled, beautiful, and respectful elevation of real tradition, not styled by the photographer but shaped by his light, his framing, and his sense of proportion. Proportion, in fact, is one of his private obsessions. He described himself as “a mathematician at heart,” loving algebra and trigonometry, and he linked taste to mathematics: balance, symmetry, the subtle corrections that make a face, or an image, click into place.

He also spoke about groups, a speciality of his, and offered a detail that felt wonderfully unglamorous: the key to directing a group is not only composition, but language. Because if you give a direction to one person, everyone moves. He liked working with people of mixed nationalities, he said, because he could address individuals in their language, keeping the room focused.

Nina, Helga, and Cindy

By the end of the conversation, the cows had gained an unexpected resonance. Testino revealed their names: Nina, Helga, and Cindy and laughed at the parallel: once, at the height of his career, the models were Kate, Claudia and Cindy. Some might bristle at the comparison, but he wasn’t equating women with animals. He was simply noticing the strange rhymes of a life spent looking and looking again.

In Gstaad, that looking felt newly concentrated. A Swiss cow, decorated like a queen, becomes the kind of portrait that forces you to slow down and pay attention, not necessarily to “Swissness,” but to dignity.

by JEANETTE WICHMANN

Follow Mario Testino on Instagram (and head the wonderful Princess Diana anecdote)

Follow PLC on Instagram