Hiking through History

05.09.2022 Arts & CultureOF STICKS AND STONES

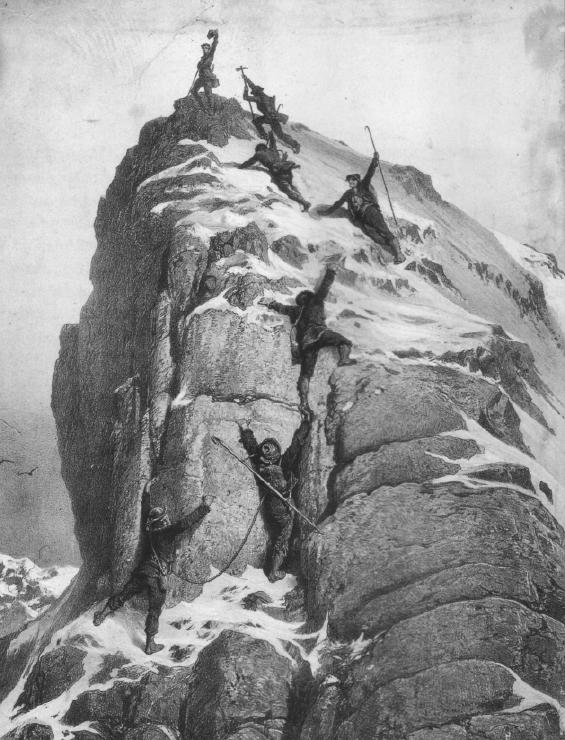

W hen tackling the peaks and high passes in Saanenland’s environs, most visitors carry handy, collapsible aluminium sticks to provide stability. But it was not always thus. Our predecessors never ascended without the ubiquitous Alpenstock.

The Alpenstock (from German: Alpen- “alpine” + Stock “stick, staff”) was a de rigeur accessory for 18th and early-19th century mountaineers in Switzerland. It was basically a long wooden pole with an iron spike tip that was used for ‘third-leg’ stability, crevasse soundings, and for pulling along climbers when traversing glaciers or ascending steep icy or snowy slopes. Its length was originally quite long, some 1.5 to 2.5 meters, and it was used in conjunction with an axe to cut steps in ice or hard snow (the combination of which eventually morphed into today’s ice axes).

No one knows the origin of the alpenstock. It was undoubtedly used by Medieval alpine shepherds crossing high glacial passes with their herds, but the indispensable mountain stick may have originated in the Roman era or even earlier. Swiss theologian Josias Simler’s 1574 work De Alpibus commentarius describes the use of the Alpenstock and primitive horseshoe-like crampons on mountain snow expeditions. When Jacques Balmat and Michel-Gabriel Paccard made the first ascent of Mont Blanc in 1786, Balmat carried both an alpenstock and an axe.

Alpenstocks gradually grew shorter throughout the 1800s and gained some new features. Charles Latrobe, the English mountaineer and statesman, carried one in August 1825 when he visited the Saanenland and stayed at the Bären in Gsteig. His book, The Alpenstock: Or Sketches of Swiss Scenery and Manners (1829), contains an image of an alpenstock with a horizontal metal pick fixed to the top. Some also had metal hooks mounted atop. Swiss geologist Franz Joseph Hugi, the “father of winter mountaineering,” depicted three different types of alpenstocks in his Naturhistorisches Alpenreise (1830): those with hooks, picks, and unadorned.

Literary mentions of the alpenstock abound. Edward Whymper, a member of the ill-fated British first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865, features images of every alpenstock imaginable in his 1871 Scrambles Amongst the Alps. American raconteur Mark Twain, who liberally plagiarised Whymper in his 1880 A Tramp Abroad (even copying his images!), used an alpenstock of the ‘halberd’ variety, reaching almost to about head-height and bearing a pick and a vertical axe blade. Since Twain included pictures of the hooked and other varieties in his work, many models obviously existed side-by-side for a period. Twain’s book also had some wry commentary about the prestige of the alpenstock amongst Victorian-era tourists:

You see, the alpenstock is his trophy; his name is burned upon it; and if he has climbed a hill, or jumped a brook, or traversed a brickyard with it, he has the names of those places burned upon it, too ... And observe, a man is respected in Switzerland according to his alpenstock. I found I could get no attention there while I carried an unbranded one (A Tramp Abroad, p. 216).

By the early 1900s, the traditional alpenstock had been supplanted by today’s conventional ice axe with its pick and horizontal adze, which subsequently grew shorter to the 75cm largest size seen at present. To the extent that traditional alpenstock could still be said to exist, they survive in the “spiked canes” one often sees covered in Swiss affinity badges, which are still a popular alternative to the aluminium sticks. But if one wants a glimpse of the original, the Saanen Museum has a few types tucked away on the upper floors. It’s worth a climb to see these classics of mountaineering history.

ALEX BERTEA