When houses speak

18.01.2021 Arts & CultureOld houses can speak in many ways. Their facades and inscriptions make statements to the eyes of the observer. But they also communicate with sound.

Dawn breaks over the peaks of the Saanenland, and the conversation begins. Creak, groan, pop. As the sun’s rays warm the ancient timbers, the conversation warms up too. Gerk, gik, eep. Old farmhouses, browned by thousands of turns around earth’s axis, rouse themselves from nocturnal slumbers and get downright chatty.

There’s a reason for this. In your typical Saanenland farmhouse of a certain age, the timber beams fit together snugly, utilizing mortise and tenon, tongue and groove, with square notching on the corners of squared-off logs on the upper stories. Through millennia of probably trial-and-error development, these buildings were designed to settle and move within their fixed context, almost breathing as they expanded and contracted according to season, temperature, and humidity.

In his two works on 16th- and 17th-century Saanenland houses, Die Zimmermannsgotik im Saanenland (1972) and Das Saanerhaus des 17. Jahrhunderts (1975), author Christian Rubi describes the incredible spirit and accomplishments of the master carpenters of that period and delves with enthusiastic detail into their techniques. They created masterpieces on wood canvases, living sculptures in harmony with their surroundings; structures superior, perhaps, to any mere painting or statue because they also provided their inhabitants a home.

Your Early Modern farmer from Saanen would have collected felled wood from his own forest if possible, often over the course of several years, which was roughly hewn on the spot in a process called walden. When the master carpenter determined enough wood had been collected, his subordinates would begin working with their heavy hatchets (Hauaxt), broad axes (Breitaxt), and planes (Hobel and Nuthobel) to shape the timbers, allowing constructors to fit the pieces together with a precision and in a manner about which today’s Ikea could only dream.

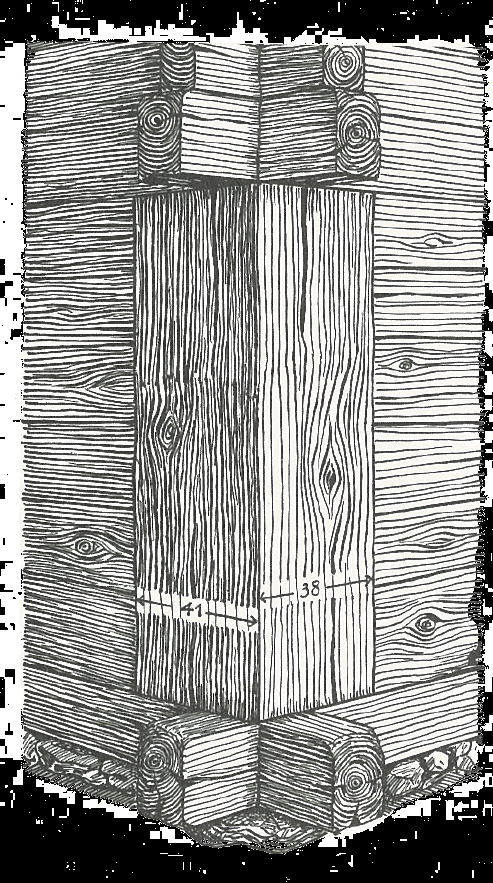

Over the stone cellar, the first residential storey (Wohnring) was erected in what in English would be called the ‘post-and-plank’ method (Ständerbau), although that denigrates the beauty of it. Thick beams with shaped tongues were precisely fitted into post (Eck- und Mittelstollen) grooves, expansion joints leaving a smidge of play as the house swelled during hot, humid weather. And all this done without iron nails, just some wooden pegs.

There’s a long history behind the technique. Archeological remains of post-and-beam wells were found in the Czech Republic dating back to the Early Neolithic (5255 BC), knowledge of which may have been dispersed throughout Europe at the time. Since the oldest dated house in the Saanenland was built in 1533, this really puts things in perspective.

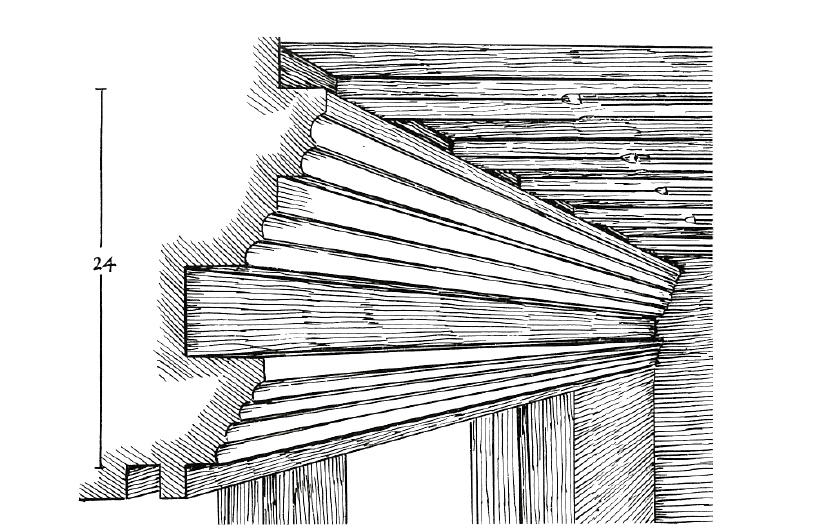

The next storey was constructed using squared-off logs laid horizontally (Blockbau, or locally Gwättbau). This took longer, as the beams had to be cut on the spot to ensure air and water tightness. This method also allowed for creative embellishment. The Thirty Years War (1618 – 1648) had brought significant money to the valley in the form of cattle and cheese sales (all those armies got hungry), so there was plenty to spend on the decorative trim for which these old houses are famous.

A stroll down Gstaad’s Promenade reveals that the hallowed carpentry traditions of the past are still alive and well in our valley. Chalet after chalet gives testimony to the skill and artistry of our contemporary builders, who take extreme pride in their work. Take a moment to sit and observe these organic objets d’art, paeans to domestic expression that populate our green sanctuary. And listen to what they tell you.

ALEX BERTEA