For whom the cockerel crows

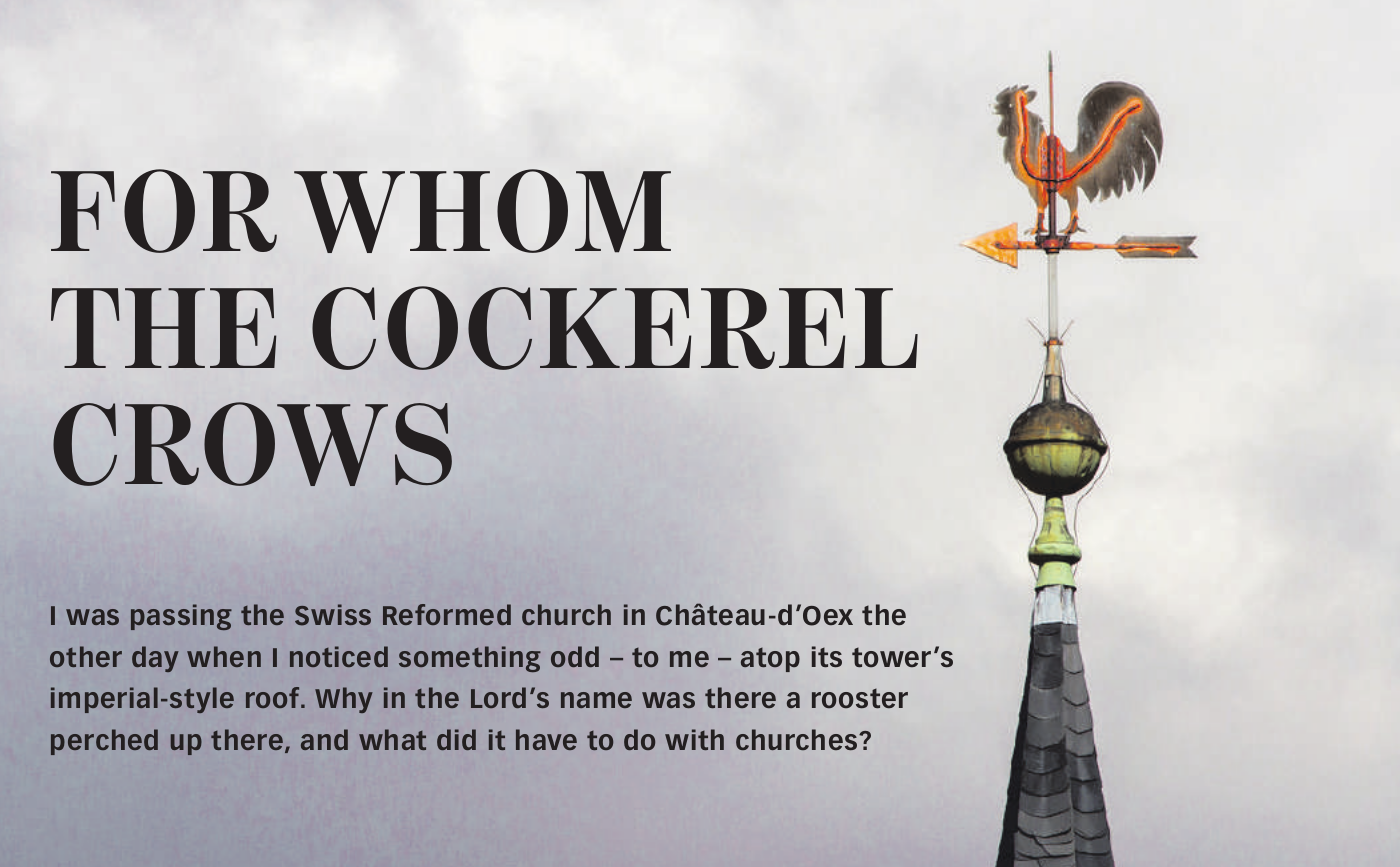

20.08.2020 Arts & CultureI was passing the Swiss Reformed church in Château-d’Oex the other day when I noticed something odd – to me – atop its tower’s imperial-style roof. Why in the Lord’s name was there a rooster perched up there, and what did it have to do with churches?

T he rooster’s journey from wild forest dweller to culinary staple and Christian religious icon is an unexpected one. The chicken’s wild progenitor is the red junglefowl, Gallus gallus, whose Southeast Asian habitat stretches from northeastern India to the Philippines, and which is thought to have interbred with at least one closely related species to produce the domesticated chicken between 7,000 and 10,000 years ago.

About 4,000 years ago, evidence suggests that city-states in the Indus Valley began to spread the chicken westward, and by 2,000 B.C., Mesopotamia tablets refer to an exotic fowl that may have been the chicken. Some 250 years later, roosters surface as fighting birds in Egypt, while finally appearing around the Mediterranean circa 800 B.C.

Novelly perhaps for contemporary palates, the early Romans considered the chicken a gourmet delicacy, but this esteem apparently did not survive the collapse of their empire in Europe, the fowl’s status diminishing in favour of hardier geese and partridges on Medieval tables. Theologically speaking, however, the chicken’s stock was on the rise. All four Gospels of the Christian New Testament record that Christ told his disciple Peter that he would deny him three times “before the rooster crows.” Peter rejected the possibility, but went on to thricely deny his association with Jesus when questioned by bystanders until a rooster crowed in the dawn. Recalling Christ’s admonition, Peter wept in repentance and was later restored as the leader of the Apostles after the Resurrection, and subsequently became the first bishop of Rome, or pope.

The cockerel’s correlation with Peter was allegedly sanctified by Pope Gregory I (590–604 AD), who purportedly described it as “the most suitable emblem of Christianity.” Pope Leo IV (70–855 AD) installed a rooster over Old St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, and Pope Nicholas I (800–867 AD) may have decreed that all churches mount the cock symbol on their domes or spires, although apparently no record of this survives and observance of it faded over time. Many roosters seem to have been fitted as weathercocks, the oldest known being the Gallo di Ramperto (820–830 AD) from Brescia, thus giving rise to the common practice of roosters on weathervanes. Protestant use of the rooster seems to date to the Reformation, and its adherents’ resistance to the use of the cross by the Catholic Church. Bern became Reformed in 1528, and its subject territories were converted to Protestantism by decree. The Saanenland and the Pays-d’Enhaut were acquired by the Bernese in 1556, after the last Count of Gruyère went bankrupt.

So why don’t all the Protestant churches in the Saanenland regions have roosters on them? Saanen, Gstaad, Gsteig and Lauenen’s Reformed churches all sport crosses. Lenk had both a cockerel and a cross, but the former was removed in 1949. In the Pays-d’Enhaut, Château-d’Oex and Rossinière have only cockerels, while Rougemont has both on its spire.

Apparently, in the rooster-cross stakes it’s not an either-or thing. Most Reformed churches have a cross, some only have roosters, several have both. Perhaps we can stipulate that if a church has a rooster, it is most likely Protestant, while those bearing only crosses could belong to any denomination.

Just another reason not to judge a church by its steeple.

ALEX BERTEA