The ungraspable garments of gods

11.02.2020 Arts & CultureBut between this love-hate dichotomy, the Föhn provokes a range of strong emotions that inspire literary and poetic musings, and can torment the senses, both psychologically and physically.

Generically, a Föhn is “a warm, dry wind that descends in the lee of a mountain range.” The south Föhn (Südföhn), which blows northward in the Saanenland, usually happens when moist air causes precipitation to build up against the Alps in the south, but it can also occasionally occur without the preceding rain. Its initiating mechanisms include synoptic pressure fields, orography, and adiabatic compression, and although scientists have been arguing about its exact characteristics since the early 1800s, it seems wise to sidestep that debate.

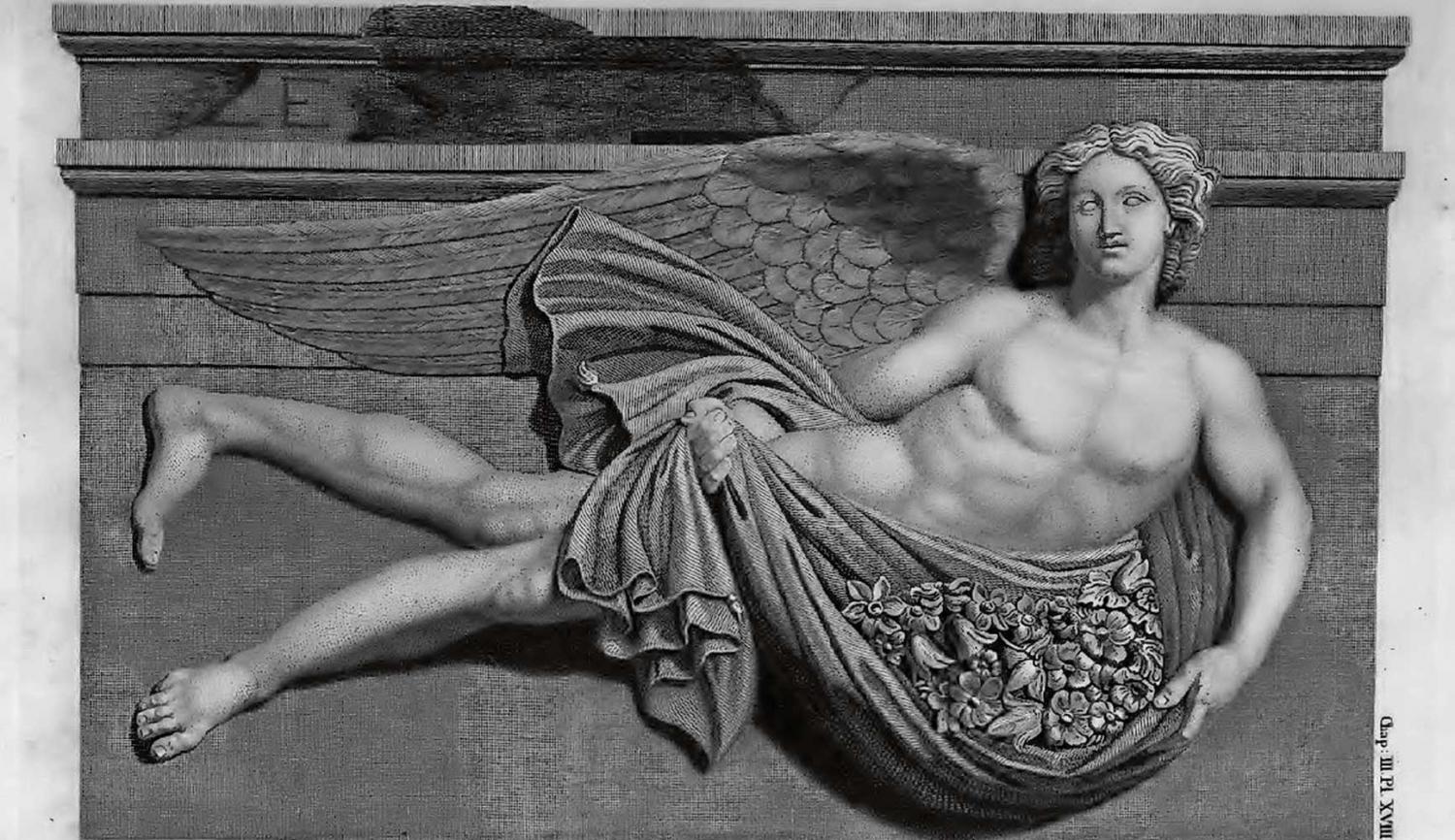

The term Föhn comes from the Latin ventus favonius, a version of the Greek Zephyr, or west wind, that the Roman god Favonius personified. The earliest mention seems to be from the Roman poet Horace (65-8 BC), who waxed about Favonius in his Odes (1.4), saying the “touch of Zephyr and of Spring has loosen’d Winter’s thrall.” But, by whatever linguistic path Horace’s wind transformed into the Föhn, he was clearly not talking about the Alpine version, which comes hurling in from the south with something more than a ‘touch’.

The vehemence of Favonius’ gauzy garments have stirred ample expressive accounts. Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell (1804) has the protagonist using the Föhn to help a refugee escape the clutches of the Austrian Gessler on the Lake of Lucerne. In Hans Christian Andersen’s fairytale The Ice Maiden (1862), he called it “an African wind” that scattered the clouds into fantastic shapes. Hermann Hesse, in his first novel Peter Camenzind (1904), extolled the “sweet Föhn fever” (Das süße Föhnfieber) of spring that gave the mountain air a crystalline clarity, and especially tormented women by robbing them of their sleep and caressing all their senses.

But the brush of Favonius’ cloak has a darker side, the so-called morbus ventus favoni or ‘Föhn disease’. Anxiety, headaches, flushing, shortness of breath, heart palpitation, insomnia, tinnitus, loose bowel movements, diarrhea, excessively rapid digestion, and “increased sexual desire with premature deflation of semen," have all been attributed to this maligned wind. Popular belief accredits the Föhn with increased car accidents, suicide attempts, strokes and heart attacks. It has even, apparently, been used as reasonable cause for insanity in a legal defense.

Is there any scientific basis to this? Numerous medical studies have been conducted on the effects of the Föhn, accreting around a few main theories. One hypothesis holds that positively charged air ions created by the wind elevate levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin, which plays a major role in emotional disorders. Others have looked at infrasound, or sound levels below the level of human hearing that can cause anxiety and physical symptoms in susceptible populations. A recent conjecture from scientists at ETH Zürich posits the Föhn’s effects may be due to rapid atmospheric pressure fluctuations induced by climate-related gravity waves that can disrupt human mental activity.

Regardless of its manifestations, the Föhn’s effect on the Saanenland certainly has not dampened the winter holidays – Gstaad Saanenland Tourismus reported record-breaking figures at hotels, restaurants, and ski lifts from 26 December to 2 January. There is even talk about building new parking structures to handle all the traffic. So whatever other anxiety this weather phenomenon has produced recently, it is not currently presenting at our local ski lift’s till.

Alex Bertea