The Saanenland’s original street art

20.08.2019 Arts & CultureBut the history of personal heraldry, a system of visual identification of individuals that was passed from one generation to the next is a much younger phenomenon, developing in the mid-12th century. The colorful heraldic shields (Wappen) that adorn many chalets in the Saanenland are younger still, and make up part of the lively héraldique paysanne of the Swiss.

Traditional European heraldry is thought to have begun in the 12th century AD, with Raoul I, Count of Vermandois, credited by many as having the first true heraldic arms c. 1135 AD. Earlier imagery, such as the Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1077 AD), did show heraldic-type devices on shields, but no individual is depicted bearing the same arms twice, and sometimes the same device is used by opposing forces!

Heraldry is thought to have originated for military, rather than nobiliary, purposes. Fighters were unrecognizable under the closed helmets of that period, which led them to paint their emblems on shields so retainers and heralds could identify them. After all, you would want to be certain that the opponent you were about to skewer on your lance was the right one.

Bartolo da Sassoferrato, a medieval Italian jurist, who wrote the first treatise on heraldry c. 1355, concluded that any man can assume arms as he pleases, subject to the proviso that he does not harm another. In fact, until the first grant of arms by the Duke of Bourbon in 1334, all coats of arms were either self-assumed or inherited through families. Heraldry gradually spread from the nobility to other strata of society, and by the 14th century Swiss burghers, tradesmen and peasants were displaying their own coats of arms. No Swiss canton has granted a coat of arms to any of its subjects, but some Swiss received arms from foreign territorial sovereigns.

Wappen

The Wappen, or coats of arms, of the Saanenland are vivid examples of burgher or peasant heraldry that thrive to this day. In a time when many could not read, they were used primarily as a sign of ownership for residences and goods. The oldest coats of arms of Saanen families are on the third picture of the life of St. Mauritius painted in the choir of the church of Saanen, which was built around 1480, although today only the families of Hugi, Jouner and Mezener can be identified.

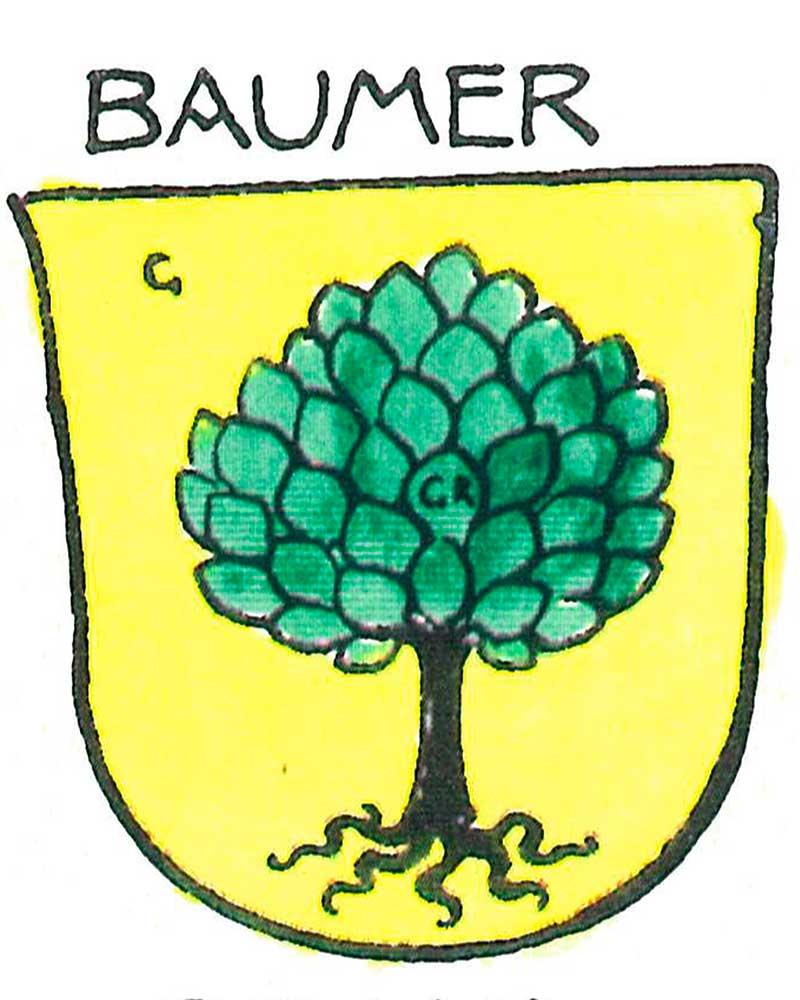

Works by Robert Marti-Wehren (1946, 1949) and J R D Zwahlen (1967) give historically annotated drawings of local armory. Black-and-white depictions of Saanenland arms in the treatises bear small letters in certain sections, a display technique called ‘tricking’, which allows viewers to understand what colors the images contain.

Canting Arms

Canting arms are shields that represent the bearer’s name, or some other attribute or function, in a visual pun or rebus. The Reichenbach arms display a curvy river with fish (Reichenbach = ‘rich stream’), Baumer a tree (from Baum), Gyger a violin (from Geige), Hauswirth (Wirt = innkeeper) an inn, and the Brand arms feature two fiery brands.

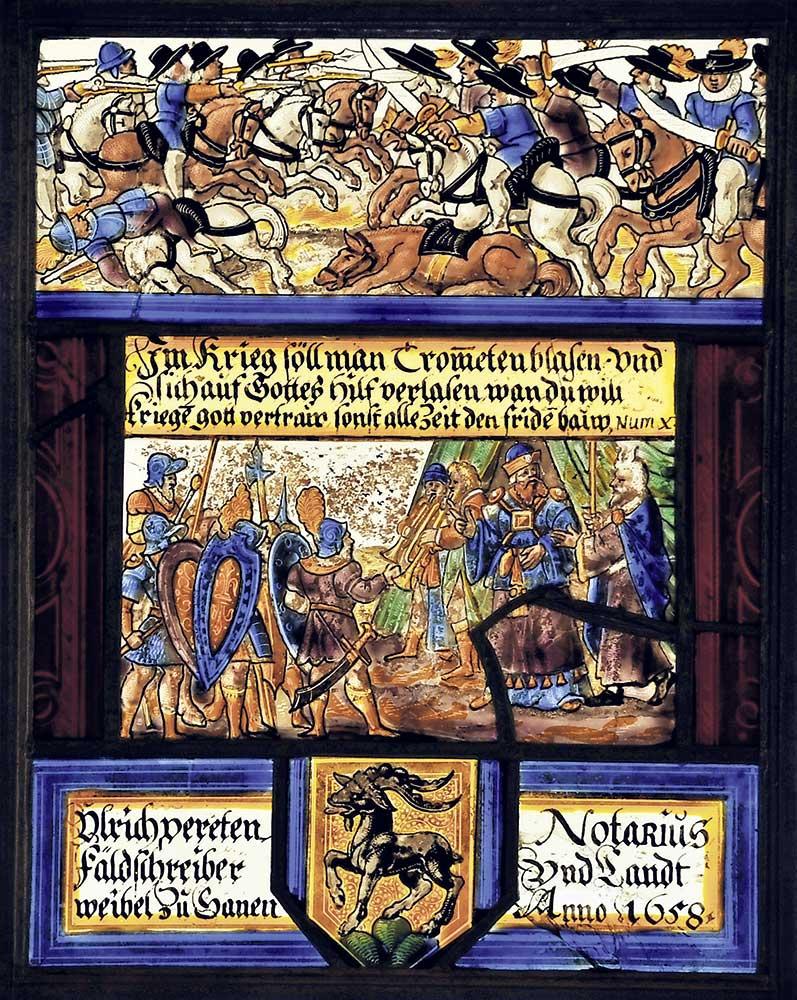

Presentations in Glass

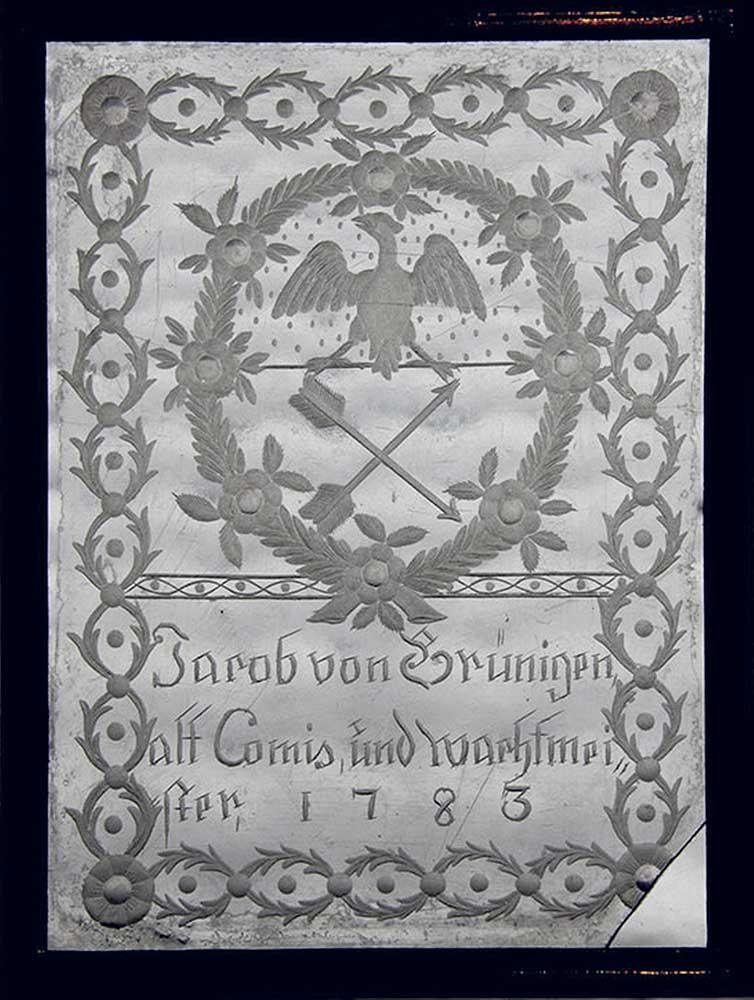

In the 17th century, individual and family Wappen were often depicted in small, but expensive, colored single stained glass panel, which were commissioned by local gentry and given as gifts of honor to a nobleman or to an honorable fellow citizen upon the construction of a new house. But because the stained-glass panels were pricey, and could darken a room, in the early 18th century transparent engraved glass panes called Schliffscheiben became fashionable. The style was likely brought to Switzerland from Bohemia or Silesia and was a reasonably-priced alternative to stained glass.

In the early 19th century, engraved glass fell from favor, and, in a style that Marti-Wehren (1946) believed may be unique to the Saanenland, glass panes painted with chalk and turpentine oil became popular. These so-called Kreidescheiben resembled the engraved glass, and were much less expensive. Recipients of the donated panes would treat the giver to a meal, which was called a Fenstermahl (window feast).

Stree art today

In modern society, taggers and stencilers supply most of the street art, and, unsurprisingly, it rarely features a coat of arms. But they don’t spray their messages on their own houses, instead claiming the streets and quarters as their territory. However, it all stems from the same foundation – ownership and pride of place. And since quite a few Saanenland families have been here for over 700 years, that pride runs long and deep.

Alex Bertea